Faith & Democracy #1: “Come to Selma!”

What the Famed March to Montgomery Has to Teach Us About the Intersection of Faith and Democracy.

Alabama, 1965.

600 or so marchers had attempted to walk from Selma to Montgomery, an action prompted by the death of Jimmie Lee Jackson, a church deacon, killed by Alabama State Trooper James Fowler.

Law enforcement was called up to quash a small group that included Jimmie and his mother. Their crime? Simply encouraging African Americans to register to vote. The group was beaten with batons, and Jimmie, who’d flung his body on top of his mom to shield her from the blows, was shot, execution-style.

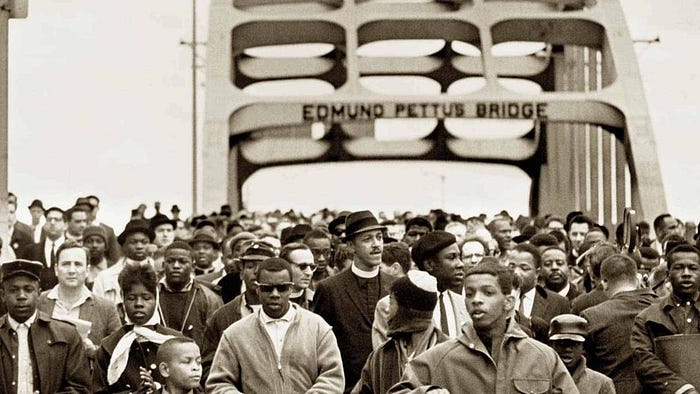

The subsequent march, which took up the cause for which Jimmie was killed, was declared illegal, and marchers, met by a massive contingent of troopers on horseback and wielding whips, and by a deputized mob carrying guns and clubs, were attacked and brutally beaten on what came to be known as Bloody Sunday.

Blocked from crossing the Edmund Pettus Bridge and essentially trapped in Selma, Martin Luther King put out the call to clergy of all faiths and from all parts of the nation — to ministers of every ethnicity, but especially white-identifying ministers — to get off the sidelines and join the struggle. “Come to Selma,” Martin implored.

And they did, thousands strong, converging on a town many of them had never even heard of until then. That’s because something clicked for them. We Americans grasped that though this seemed to be about a tiny group of Negroes in a southern town, it was really about something else entirely. It was about us as a nation and the saving of our collective soul. And in that moment, humanitarian spiritual activism, the same torch that stoked the fires that led to slavery’s end a century earlier was reignited.

Alabama, 1978.

I was 13 years old when I opted to canvas Anglo neighborhoods in Birmingham and speak in historically white churches on behalf of Richard Arrington who was vying to become the city’s first African American mayor just 15 years after fire hoses and police dogs had been turned on children. Their crime? Simply for assembling when they’d been told not to, and for daring to walk from Sixteenth Street Baptist Church downtown while singing spirituals.

My mother, who was arrested along with Martin and hundreds of others, was one of those children. It just so happens that she was also 13 at the time. I’m glad to have followed in her footsteps in my own way. Dr. Arrington won the election, and in doing so, made history. (You can read more about my experience knocking on doors here, in a vignette from This Land Is Your Land titled, Sister Rose, or the Power of “We”.)

But, in many ways, Arrington’s victory, history-making as it was, is beside the point. The real point is that he achieved this victory at a time when African Americans were still a minority in Birmingham, which meant that the only way he could have won was with support that extended beyond the black community.

Thirty years later, I was bringing the lessons I’d learned from that experience and others like it to an equally historic campaign — Barack Obama’s 2008 presidential run. My contributions weren’t all that different from those days in Birmingham, except this time, I was galvanizing pastors across the entire nation instead of congregations in just one city. But the work was essentially the same.

My experience as an African American raised in a home where my grandfather was one of the ministers who appealed to Martin to come to Birmingham, and where I’d taken my message of Richard Arrington’s pledge to help us become a Birmingham for all Birminghamians to many of the city’s largest Southern Baptist churches, which, at that time, meant “segregated and white”, prepared me immensely well for that work.

Then, there was my vocational training. By then, I’d long graduated from a Southern Baptist seminary, had been an adjunct professor at that seminary, and, as a young African American minister in a mostly white-identifying congregation and denomination, I was a bit of a rising star.

This all meant that, from all sides, I had a visceral, lifelong understanding of the power that faith could have to either unite us or divide us, to strengthen or weaken us, make us or break us. I wanted to help us use that power for the former instead of the latter. That meant adopting a three-pronged strategy for my work within the campaign:

1) Challenging Democrats to commit to building bridges instead of barriers and to going after every vote, including the evangelical vote, rather than simply assuming they were all going to vote Republican,

2) Reaching out to historically white congregations of all faiths to help them see how this was an unprecedented opportunity for us Americans to take a step into a better future for all of us, creating an America for all Americans, and

3) Empowering pastors working in non-Anglo and lower-income communities to help their congregants to understand the tremendous power that the vote gave them, and to encourage them to use that power.

I’m immensely proud of what that work meant, not just for the election, but for us as a people. For instance, many of these same ministers would also join Clergy Against Prop 8, a multi-faith coalition I co-founded, and that sought to prevent the passage of Proposition 8, a ballot measure written to make same-sex marriages, which had been legal for four years in California illegal.

The measure passed, but only barely so, thanks to the work of ministers and faith groups like these, and they’d join the groundswell that would ensure that similar measures would never be passed again. Then, in 2020, members of that coalition, many of whom had reached retirement age, would come together once again; this time to form a Wall of Clergy that positioned itself between protestors in Portland and federal troops sent by a sitting president to oppose them.

United States, 2024.

Today, those fevered, 1960s speeches rooted in white nationalism, ones where even governors proclaimed, “Segregation today, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever,” or where white supremacists declared “Our Race Is Our Nation (O.R.I.O.N.) are all but gone.

But make no mistake — the rhetoric’s core driver hasn’t actually gone anywhere. The sentiments haven’t disappeared. They’ve simply molted, just as they did when a faction shed the no-longer-relevant “slave/free” paradigm after slavery was abolished, and adopted one based on “whites” and “coloreds”. They did the same thing after segregation was made illegal; this time, trading “White is Right” for “Take the country for God”.

Today, the same toxic ideology is increasingly packaged in religious instead of racial language, worked into sermons instead of speeches by politicians. But no matter how it’s packaged, the mindset’s destructive results remain the same.

Next year marks the 60th anniversary of the call that went out from Selma to people of faith and goodwill all over America. And as we approach this pivotal moment in history, reflecting on everything from that fateful bridge to the horrific beatings, the one thing we must never, ever forget is that when it mattered most, we Americans answered the call.

Remember that people from across the nation, of every ethnicity and ancestry, every age and every political affiliation, every gender and sexuality, came to Selma. Remember that the four people who lost their lives were all people of faith.

Jimmie Lee Jackson, whose execution by law enforcement prompted the entire march, was a Baptist deacon. Rev. James Reeb, a Unitarian minister and personal friend of Martin’s, was beaten to death by an angry mob who saw him, simply for daring to show up there in that place at that time as a “traitor to his race”.

Third was Jonathan Daniels, a 26-year-old Euro American and Episcopal seminarian. Jonathan used his body to shield Ruby Sales, a 17-year-old African American fellow marcher from a shotgun blast. He was killed instantly. And finally, there was Viola Liuzzo, a Unitarian whose only offense was being a white-presenting woman ferrying activists back to the Montgomery airport after the march.

Four KKK members ran her off the road and shot her twice in the head. Later, the Birmingham News would publish an ad from someone attempting to sell her car. Asking for $3,500, the listing said: Do you need a crowd-getter? I have a 1963 Oldsmobile two-door in which Mrs. Viola Liuzzo was killed. Bullet holes and everything intact. Ideal to bring in crowds.

But even in their deaths, they’d triumph. Their lives would serve as much-needed reminders that humanitarian faith has always heeded the call, standing in opposition to the kind of faith that’s been co-opted by advantagism. They’d fortify our collective conviction and endow tens of thousands with unbreakable resolve. They’d embolden everyday people to stand up and step up.

And in doing so, we Americans would do far more than come to the aid of our societal kin, we’d move the entire nation one step closer to being, as President Lincoln said, “a nation that can endure”. “It’s gonna happen, Granddaddy,” said Bob Zellner to his Klan grandfather in the 2021 film, Son of the South. “I’ve met the people changing everything and they’re… You can’t stop them. They are tougher, they are stronger, they’re more resilient, and they’re right.”

Christian Nationalists say we’ve lost our faith and our way. But today, just like in Selma, we have Americans from every corner of the country, across political parties and from every faith tradition; people of every ancestry and gender, age and sexuality, all standing up and showing up. Whether marching on the streets or to the voting booth, whether lifting up the downtrodden or resisting injustice, we’re taking up the charge and completing Selma’s unfinished work.

And in doing so, we, like them, move the entire nation one step closer to being a better America, a place where we all can thrive; a land made for both you and me. If that’s not faith, I don’t know what is.

—

Faith and Democracy is an open series of articles that explore this pivotal point in our nation’s history, the longstanding role that faith and spirituality, both for better and worse, have played in shaping the society we’ve become and are becoming.

RD Moore is an artist, minister, lifelong social activist, emancipationist and founder of the Mary Moore Institute for Diversity, Humanity & Social Justice (MMI). He credits the people who crossed his path starting in his formative years in post-Civil Rights-era Birmingham for the person he’d become and for his unyielding faith in who we can be together. Known for his intimate storytelling and insightful understanding, his work continues to explore that fertile space where diversity, spirituality and humanity all intersect. His blog, Letters from a Birmingham Boy, can be found here.