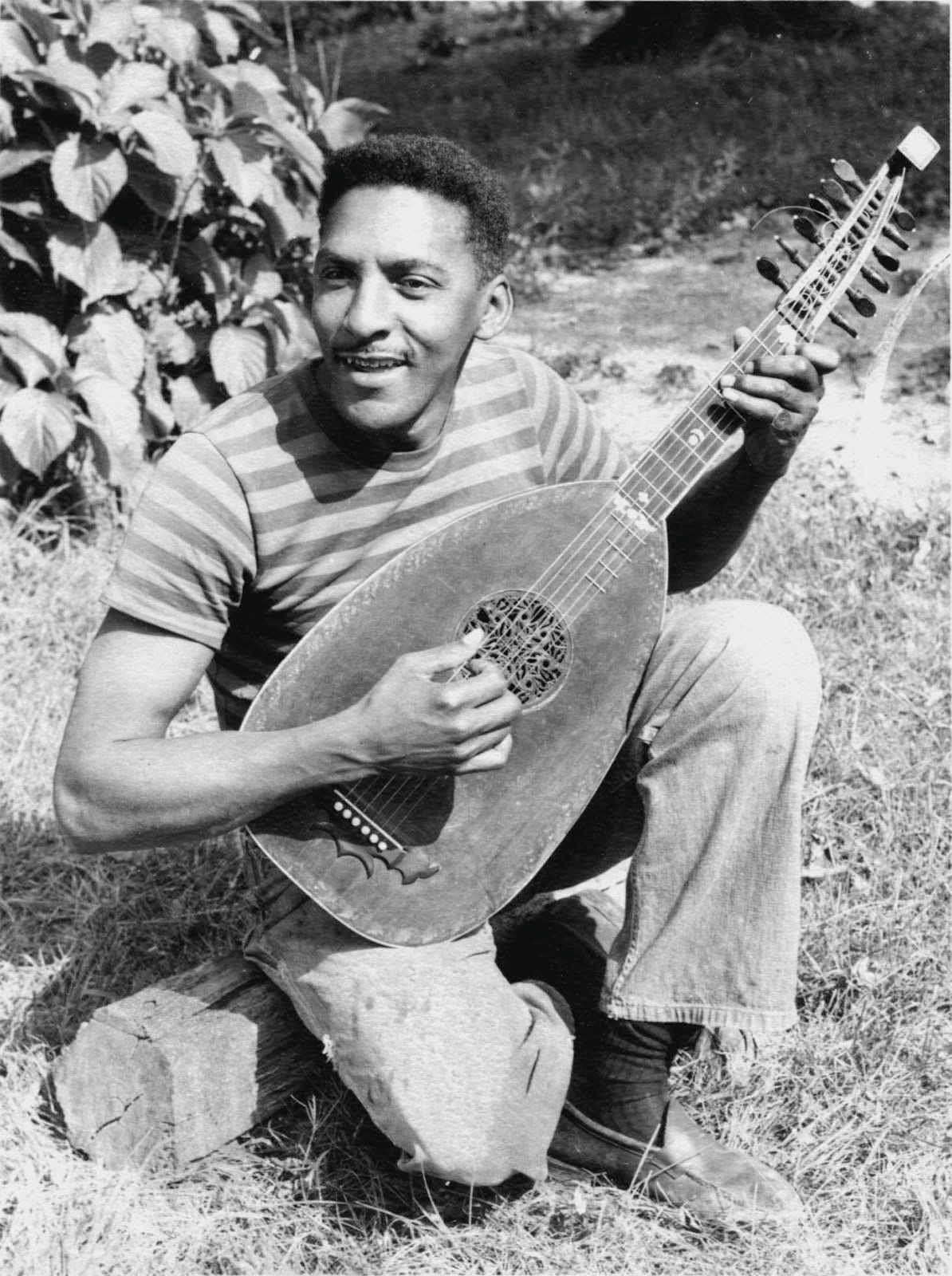

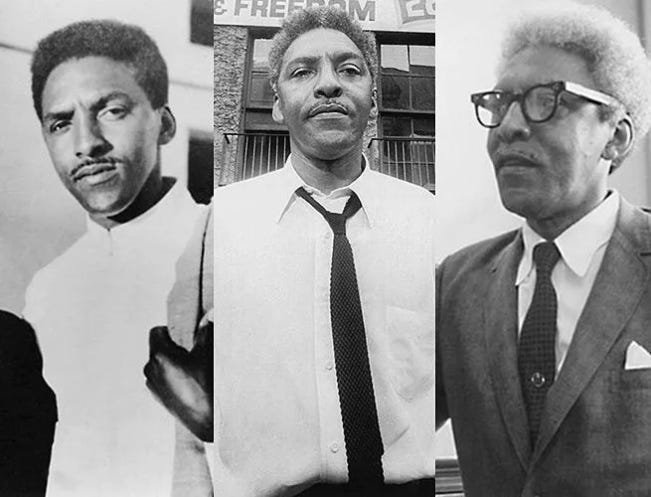

Bayard Rustin, the gay civil rights leader who, despite enduring discrimination and rejection from his own associates, went on to become a primary driver behind much of what made the movement successful; who introduced Martin to Gandhian tactics and the concepts of nonviolence; who conceived of the idea of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference; and who masterminded the March on Washington, at the time unprecedented in size and magnitude and certainly the largest public assembly of Negroes we’d ever seen, might very well be the most influential unsung American hero in the last century. He’s also my personal hero. In the preface of This Land Is Your Land, I describe him this way:

As a kid, I was often called nicknames like “Professor” or “Little Preacher” — the former for my horn-rimmed glasses, and the latter, perhaps because even back then, I was such an avid evangelist for the philosophy that Martin and others espoused. I was very much a true believer; in the principles undergirding the cause, that the world could be a better place, and that each of us had the power to make it so. I’d grow up, however, to find I have far more in common with Bayard Rustin; the gay, unassuming, unsung hero of the Civil Rights movement who stood in the background instead of the spotlight.

A man who, like me, had to struggle to be a whole person, to embrace his ancestry, his sexuality, and his spirituality, even as others, in every group, rejected what didn’t reflect them. Nevertheless, it was Bayard, in many ways, the conscience of the movement, who originally introduced a young Martin to nonviolent resistance, who, through initiatives like the Freedom Riders, made direct social action an interracial effort, and who, perhaps more than anyone, infused the movement with compassion, humanity and inclusion. I would be well into my 30s before even embarking upon the kind of self-embracing that Bayard, as a teen, had already mastered.

Born March 17, 1912, Bayard, like me, was raised by his maternal grandparents in a quietly religious household (Quaker for him, Baptist for me), where the values of nonviolence, peace and acceptance were infused into his core. From the warmth of his childhood home to his religious community, he’d grow up in a remarkable space for the time, one where all aspects of his personhood, including his sexuality, were affirmed by his community. This, in turn, would endow Bayard with an unshakable sense of self-acceptance and confidence, a deep reservoir of empathy and human regard, and an unwavering resolve to be a force for good in the world.

His family’s role as prominent members of the newly formed NAACP meant that from his earliest memories, people like W. E. B. Du Bois, Ida B. Wells and Chairman Spingarn were around the dinner table. (I was blessed in a similar, though far less spectacular way, growing up within walking distance of the Birmingham Jail and Sixteenth Street Baptist Church, where people gathered to mourn racial injustice, and in a family that was deeply involved in Birmingham’s civil rights effort, so I get what a difference growing up in an environment like this can make.) For Bayard, those early influences were pivotal in his efforts, even as a boy, to become an activist.

In 1932, he enrolled in Wilberforce University, only to be expelled three years later after organizing a strike, then later attended Cheyney State Teachers College. The next year, after completing an activist training program conducted by the Quaker-based American Friends Service Committee, he moved to Harlem, where he got involved in efforts to defend and free the Scottsboro Boys; nine African American young men in Alabama who were falsely accused and wrongly convicted of raping two white-identifying women.

Two other important things happened shortly after his arrival in Manhattan. First, he officially became a member of the East Village’s Fifteenth Street Meeting of the Religious Society of Friends/Quakers, a focal point of social justice in NYC. And second, he’d meet one of the most influential figures in his life: A. Philip Randolph, head of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters (the first chartered African American labor union), who would become his lifetime mentor.

In 1939, Bayard, along with colleagues George Houser (Anglo) and James Farmer (Negro),all of whom would be instrumental to the civil rights struggle, would find themselves utterly transformed by Krishnalal Shridharani’s newly published Columbia University Doctoral thesis, War Without Violence; a codification of Mahatma Mohandas Gandhi’s organizing techniques and ideas on nonviolent civil disobedience. Everything they did from then on would be influenced by those writings.

The Fellowship of Reconciliation (FOR), in the late summer of 1941, would hire Bayard as Race Relation Secretary, and Bayard, along with A. Philip Randolph and Dutch-born pastor and FOR co-founder A.J. Muste, would, together, be the first to propose a march on Washington. Intended to protest racial segregation in the armed forces and widespread discrimination in employment, A. Philip, meeting with President Roosevelt in the White House’s Oval Office, courteously but firmly informed him of plans for the march and why it was needed.

The president, hoping to avoid a shift of focus on the eve of war, issued Executive Order 8802, which banned discrimination in defense industries and federal agencies. A. Philip, as a show of good faith, cancelled the march, though Bayard had misgivings. His concern was that military discrimination, one of the core drivers of the march, would not end without political pressure to do so. And on that point, he was right. The armed forces would not be desegregated until 1948, three years after the end of the war, and under an Executive Order issued by President Truman.

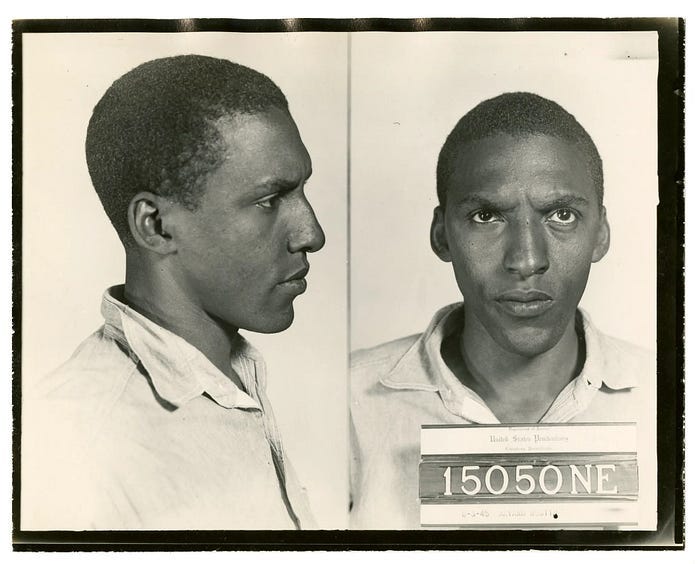

With a sense of concern that extended far beyond the interests of African Americans, it was Bayard’s deep reservoir of humanity, a constant presence in his life, that compelled him to travel to San Francisco where he helped protect the property of the more than 120,000 Japanese, most native-born Americans, who had been unfairly imprisoned in internment camps. In 1942, on a bus from Kentucky to Nashville, Bayard would, on impulse, take a courageous stand that, five years later, would lead to an entirely new form of nonviolent protest; the Freedom Ride.

Upon boarding and paying, Bayard, even as he started walking down the aisle to the colored section, stopped, turned around, and took a seat in the second row; the white section. After refusing several requests from the driver to move to the back, his bus was stopped 13 miles outside of Nashville. Bayard was arrested, beaten and taken to the police station, before finally being released, uncharged. He would later speak about how this galvanizing moment occurred:

As I was going by the second seat to go to the rear, a white child reached out for the ring necktie I was wearing and pulled it, whereupon its mother said, “Don’t touch a nigger.” If I go and sit quietly at the back of that bus now, that child, who was so innocent of race relations that it was going to play with me, will have seen so many blacks go in the back and sit down quietly that it’s going to end up saying, “They like it back there, I’ve never seen anybody protest against it.” I owe it to that child, not only to my own dignity, I owe it to that child, that it should be educated to know that blacks do not want to sit in the back, and therefore I should get arrested, letting all these white people in the bus know that I do not accept that .

In the interview, he would go on to explain how this same logic applied to his sexuality and coming out, describing it as “an absolute necessity”. Because if I didn’t,” he continued, “I was a part of the prejudice. I was aiding and abetting the prejudice that was a part of the effort to destroy me.” Once again, it was his awareness of humanity; both others and his own, that propelled him into action.

That same year, Bayard would serve as advisor to key Fellowship of Reconciliation staff members in their quest to devise new, more potent ways of promoting societal change, an effort that resulted in the birth of CORE (Congress of Racial Equality). The interracial (roughly one-third colored and two-thirds Caucasian), mixed gender (28 men and 22 women), 50-member group was convened by George and James, who, along with Bayard, were devoted believers in Gandhian nonviolent resistance.

At the time of CORE’s founding, Gandhi was still challenging British rule in India, and making headway. Bayard, George and James were all convinced that similar tactics could be used against racial oppression here in the United States. The 1947 Journey of Reconciliation and precursor to the Freedom Ride was a two-week-long, non-violent direct action that challenged segregation on interstate buses, based on Bayard’s earlier experience. The goal was to demand enforcement of the earlier Supreme Court decision that banned segregation on any public transportation travelling across state lines.

Bayard, one of 16 men, eight Anglo and eight Negro, embarked on the two-week journey on April 9, 1947. The group purposely disregarded segregated seating notices with Coloreds sitting up front, Caucasians sitting in the back, and sharing seats throughout the trip. Starting in Washington, DC, they made it all the way to Durham, where the bus driver called the police after Bayard refused to move to the back of the bus.

No arrests were issued during that encounter, but three days later, as the bus was leaving Chapel Hill for Greensboro, four of the men, Bayard and one other Negro Rider, along with their Anglo seat-partners, would be pulled from a cross-country Trailways bus, arrested, and sentenced to 30–90 days on chain gangs. Bayard’s writings about the experience would serve as inspiration to the NAACP, including to one Rosa Parks.

Bayard would continue his work in social activism for the next decade, and in 1956, would be persuaded by A. Philip to meet with a young, promising civil rights leader staging a boycott in Montgomery, Alabama, the first such action ever tried, and to advise him on Gandhian tactics. That leader was a 26-year-old Martin Luther King.

Martin would immediately recognize not only Bayard’s powerful and compelling ethos of humanity, but his strengths as a master tactician and organizational genius; strengths that Martin, already a formidable orator and inspiring leader, lacked. Bayard’s value to both the fledgling movement and to a newly minted Rev. Dr. King were immense; so much so that they completely outweighed any concerns Martin might have had about how Bayard’s sexuality, something he’d never hidden, could potentially be used against the movement. It took only one meeting for Martin to be utterly convinced that wherever things went, the movement needed Bayard.

According to Michael G. Long, editor of I Must Resist: Bayard Rustin’s Life in Letters, and co-author of Bayard Rustin: The Invisible Activist, “Dr. King had read Gandhi, but at that point he hadn’t accepted pacifism as a way of life.” “I think it’s fair to say that Dr. King’s view of non-violent tactics was almost non-existent when the boycott began,” Bayard would later say. “In other words, Dr. King was permitting himself and his children and his home to be protected by guns.”

In conversations that spanned far beyond the particulars of making the boycott successful, Bayard engaged with Martin on the deeper questions, including what true success looked like, the best way to get there and how Martin’s actions would both set the timbre and chart the destiny of the movement. Heeding Bayard’s counsel, Martin would not only relinquish his gun, but would come to wholeheartedly embrace Gandhian philosophy, and the doctrine of nonviolence would emerge as both the cornerstone of Martin’s personal ideology and the beating heart of the Civil Rights Movement.

Bayard would go on to serve as a key leader and advisor to Martin and the movement until 1960, when, under threats by US Representative Adam Clayton Powell to leak to the press rumors of a fake affair between him and Martin, Bayard, in order to protect the movement and Martin, resigned. Bayard continued to work on a number of civil rights issues, but separate from the efforts of his brainchild organization, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), which Bayard formed, but Martin led.

The movement, in 1961, began encountering escalating incidents of violent reprisals, including assaults on Freedom Riders, and by a mob that surrounded Martin, Ralph Abernathy, and 1,500 attendees at the Montgomery church that Ralph led. As things came to a boil, this was the environment that made the success of both the Birmingham Crusade and a national march a necessary. Both A. Philip and Martin recognized that only one person could pull off something of this magnitude, especially on that time frame. They’d both run interference with everyone from other civil rights leaders to the FBI on Bayard’s behalf. And despite his many detractors, Bayard succeeded.

Originally conceived to commemorate the 100-year anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation, it was he who would turn the march into a statement, not of the past, but of the future. After passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Bayard was a primary advocate for closer ties between the Civil Rights movement and the historically racist Democratic Party, and especially the party’s white-identifying, working-class base. That year, Bayard and labor activist, Tom Kahn, would co-author the landmark article, From Protest to Politics.

Once again, tapping into his deep reservoir of humanity, Bayard, arguing against the shortsightedness of identity politics; urged the Negro community to expand its vision and to build a working-class coalition that collaborated across racial lines for common economic goals. His words were largely unheeded. Specifically, he lobbied for a change in political strategy toward building and strengthening alliances with labor unions, Elks Lodges and the like, as well as churches, synagogues, mosques, and so forth; the strategy behind “from protest to politics”.

Martin, at the time of his passing, would, once again, be traveling in Bayard’s wake, but he, even more than Bayard, would be met with both resistance and ridicule, including from much of black America. Though Martin’s hope of a Poor Peoples’ Campaign would posthumously come to fruition, the true power of this strategy was never fully embraced by the movement.

It would, however, be proven almost a decade later; by gay rights pioneer Harvey Milk. Bayard would continue to work tirelessly on the causes dear to his heart, and that elevated our sense of humanity. He sought to strengthen the nation’s labor movement, which he saw as the pathway to economic justice for all Americans, served as founder and Director of the A. Philip Randolph Institute, and in 1972, became co-chair of the Social Democrats, USA (SDUSA) political party; work that would continue throughout the rest of his life.

In a 1986 testimony on behalf of New York State’s Gay Rights bill and amidst catastrophic deaths from AIDS; deaths we Americans were set on ignoring, Bayard would give the most compelling speech of his life, one provocatively titled, The New Niggers Are Gays. “Today, blacks are no longer the litmus paper or the barometer of social change,” he would say:

Blacks are in every segment of society and there are laws that help to protect them from racial discrimination. The new ‘niggers’ are gays…. It is in this sense that gay people are the new barometer for social change…. The question of social change should be framed with the most vulnerable group in mind: Gay people.

Though breaking barriers was never his intent, Bayard might very well be America’s first openly gay public figure. Upon his death in 1987, his obituary in The New York Times included a quote from him that said: “The principal factors which influenced my life are 1) nonviolent tactics; 2) constitutional means; 3) democratic procedures; 4) respect for human personality; 5) a belief that all people are one.” This self-summation, a profound distillation of Bayard’s work, was more than that, however; it was a stirring articulation of the humanitarian spiritual core that ran, like a river, throughout his life.

The Times obit notwithstanding, Bayard’s passing, unlike so many other civil rights icons, went largely unrecognized, and his contributions, mostly unappreciated. That, however, has begun to change. Both Brother Outsider, an award-winning documentary (2003) and Rustin, an Oscar-nominated biopic (2023) tell his story. He’s been honored by the LGBTQ+ community in numerous ways, and several buildings and institutes, including in his hometown of West Chester, PA, have been named after him. And in 2013, 50 years after the March on Washington, Bayard was posthumously awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

I, for one, am immensely gratified by this. But it’s not just because of who Bayard was or who I am. It’s because of who we are, and how, in every way we rewrite people like Bayard, these paragons of humanity, back into history, we become a better people.

Luminescent is an open series about LGBTQ+ humanitarians and allies for equality. Bayard Rustin — Paragon of Humanity is the first article in the series.

—

RD Moore is an artist, minister, lifelong social activist, emancipationist and founder of the Mary Moore Institute for Diversity, Humanity & Social Justice (MMI). He credits the people who crossed his path starting in his formative years in post-Civil Rights-era Birmingham for the person he’d become and for his unyielding faith in who we can be together. Known for his intimate storytelling and insightful understanding, his work continues to explore that fertile space where diversity, spirituality and humanity all intersect. His blog, Letters from a Birmingham Boy, can be found here.