The DEI Chronicles (Part 1 of 5): “I’ll Take You There”

Why only organizations that integrate diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) into their DNA have a future in the future.

Ain’t Nobody Crying

It was in 1972 that the Staple Singers, with legendary Mavis on lead vocals, recorded their most enduring song — I’ll Take You There. “I know a place,” Mavis sang, Ain’t nobody crying, ain’t nobody worried. Ain’t no smiling faces, she continued, No lying to the races…

The “smiling faces” reference she was making traced back to the 1971 song recorded by The Undisputed Truth; Smiling Faces Sometimes:

(Beware!) Beware of the handshake that hides the snake!

(Can you dig it? Can you dig it?) I’m telling you, beware!

Beware of the pat on the back — it just might hold you back.

Jealousy (Jealousy), Misery (Misery), Envy (Envy),

I tell you, you can’t see behind — Smiling faces, smiling faces sometimes — they don’t tell the truth. Smiling faces, smiling faces tell lies — and I’ve got proof!

Both songs were imagining a better land, one where we’re all operating in good faith, where no one is “lying to the races” and where everyone can thrive. It’s this understanding, the realization that only a society made for all of us will ultimately work for any of us that makes DEI efforts — embracing diversity, equity and inclusion — so necessary. Doing so is our only way forward. And just a few years ago, it seemed that we, as a nation, were finally on our way.

In the wake of the 2020 protests, all kinds of companies rolled out diversity initiatives, making fundamental changes to how work works. For instance, a 2021 Harvard Business School report sponsored by SHRM and Trusaic discovered that diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) had emerged as a key strategic priority for nearly 70% of all US companies. But now, four years later, most of those companies have reversed course and those changes rolled back.

I, however, am not surprised — not because I’m a pessimist (I’m not) — but because while the efforts were well-intentioned, they were essentially built on the same race construct that’s driven our nation’s economic disparities since Reconstruction and that took up where slavery left off. We sought to address the outcomes while overlooking the cause — the framework that made our “lying to the races” possible. But we can’t solve our problems using the same tactics that created them in the first place.

The whole thing reminds me of an article I once read about a fire department that hired two African American firemen over Anglo candidates who did better on the written test the fire department had adopted as a screening process. The latter sued for reverse discrimination and the judge reluctantly sided with them, essentially stating that while he applauded the fire department’s effort to account for systemic inequity in their hiring process, the way to go about it was to undertake the effort of adopting a process that actually worked, rather than simply wishing away the one they had.

The lesson? Ignoring the root problem, even to do a good thing, won’t fix what’s broken. That’s one part of it. The other is that we’ve overlooked how American society itself has changed — the massive demographic shifts that have upended everything from cultural dominance to church attendance to politics and perhaps most significantly, the rise of poverty across racial lines, including working-class Anglos.

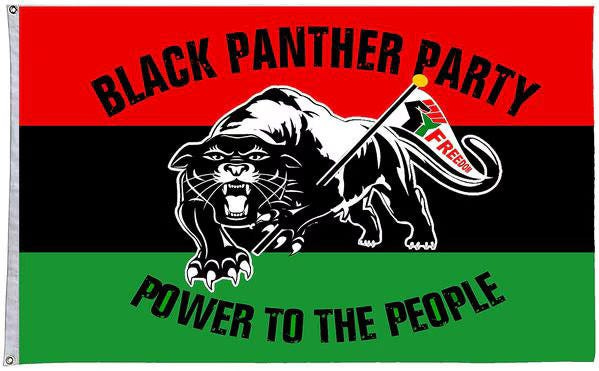

But even this isn’t new. It’s exactly why the Confederate flag-waving Young Patriots were co-founding members, along with the Black Panther Party and the Latinx Young Lords, of the original Rainbow Coalition. The groups’ leaders — Fred Hampton, Jose Cha-Cha Jimenez and William “Preacherman” Fesperman — all understood one thing — that the same impoverishing system held them all captive.

When it comes to how our economy works, we tend to want to lay the blame on big ag and big banks, big tech, big pharma and the like. But getting this right goes far beyond the corporate sector. It involves all of us. It means aligning our societal systems — from governance to faith groups, from culture to shared identity, from how we spend our money to how we choose our candidates — with the increasingly diverse people we’re becoming. That’s our only viable way forward and is how, together, we create for ourselves a future.

Way of the World

But this, creating for ourselves a future, isn’t necessarily what we’re doing. In fact, just when we should be ratcheting up and expanding the reach of our efforts to transform ourselves into a society where diversity can thrive, we’re doing the opposite, scaling those efforts back and reducing them down, tucking them neatly under the auspices of HR or treating them as another marketing initiative.

Then, there’s our sense of inflated importance and how we’ve discounted how critical restructuring the system is to our own survival. If we’re at the top of the pyramid, we tend to think of inclusion as something we’re doing for them, for “those people”, often at a cost to us. We think it’s about our benevolence — our willingness to offer them, society’s unfortunates, a bit of our abundance.

In our minds, we’re graciously sharing with them “our” jobs and economic opportunities, “our” water fountains, diner stools and seats at the front of the bus. For us, inclusion means giving them the chance to play in our sports leagues, serve in our military, attend our schools, and participate in our political process. We rightfully feel good that women are now in the C-suite, gays can get married and Muslims are in Congress.

Yet, with each concession, we can’t help but also feel a bit put-upon, as if we’re constantly being asked to give up more of what’s considered to be rightfully ours. And that’s exactly where we go wrong. Because while this might once have been the way of the world, the world itself is a different place today.

I write often about America’s GSS — our Great Sociological Shift. In fact, it seems to be the foundation of almost everything of any importance I have to say. That’s because, like the melting icecaps that are producing more hurricanes, or the collapsing biosphere which is depleting our food supply, it’s another change that’s not readily obvious, but that has already incalculably altered our lives.

We’re living in a time when the very fabric of American society is evolving and at a time when, in every way we currently measure, we’re transforming into a post-majority nation. For instance, in 2012, non-Anglo births, for the first time in US history, surpassed Anglo births, setting us on a trajectory that will render us a nation with no ethnic majority in just 20 years.

2017 was the year non-churchgoers, again, for the first time, surpassed churchgoers in the United States. And people openly identifying as LGBTQ+ has grown from 2.5% among Generation X, to 25% among Millennials, to nearly 40% among Gen Z. Generation Alpha, already our nation’s first non-Anglo-majority cohort, is also on track to be the first where more people identify as some version of non-straight rather than straight.

And this isn’t just here. This foundational shifting is happening all over the world. This new breed of humanity isn’t just diverse in ways we don’t have categories for; they’re interconnected, by everything from social media to a global economy, from culture blending to global travel, in ways we can scarcely imagine. The Alphas are not only non-majority, they’re the first non-racialized, non-genderized, non-heteronormative, non-religionized, fully diversity-embracing generation in human history.

As such, they’re radically redefining who we mean when we speak of “we, the people”. Further, this diverse constituency will soon hold the cultural, political and economic power. They’ll determine everything from who gets elected to which companies survive. All of which means that for incumbent entities, though we think today’s inclusion efforts are about creating a place for them, they aren’t. They’re about creating one for ourselves.

My acute awareness of the shift we’re undergoing stems back to the mid-90s. I was living and working in San Francisco where I, a young, soon-to-be former pastor, was nearing nearly a decade of work with the city’s AIDS victims. I’d come to realize that I’d traveled as far as I could with a denomination that was becoming increasingly strident in its declarations that AIDS was “God’s wrath” and that I and other young ministers like me had to choose — continue associating with “those people” and lose our pastoral positions or leave that work behind and return to the fold.

I’m proud to say that all of us chose the former. That was my first encounter with an institution that was becoming increasingly incompatible with the diverse people we were becoming. It wouldn’t be the last.

The System Beneath the Symptoms

It was around the time that we were just beginning to turn the corner on the AIDS crisis that the dotcom craze, our version of the gold rush, kicked off. Seemed like everyone was trying some kind of idea they hoped would make them instantly rich. I saw what was happening to the city and to its inhabitants, including those who’d held on long enough for drugs that turned HIV from a death sentence into a chronic illness to arrive. Rents skyrocketed with people flocking to live in SF, then commute by air-conditioned Google bus to Silicon Valley each day. Meanwhile, the AIDS epidemic morphed into a homelessness epidemic; one that still plagues the city today. This was my second window into the problem.

A group of social entrepreneurs brought me in to share lessons we could learn from the crisis, including the importance of infusing humanity into even mundane practices, and afterward, one of the attendees asked if I could advise their startup. I had little formal understanding of profit margins and private equity. I wasn’t the right person to help them with P/E ratios or when to buy or sell shares. But I understood one thing — that the culture of any group is an aggregate of what its individual members bring to it. And with that understanding, I could help these companies adopt practices that reflected and reinforced the humanitarian values they already held. Today, this still feels like the crux of the matter.

For me, this orientation stems all the way back to my growing up years in Birmingham. Despite being known as the “most racist city in America,” in an America that was itself deeply troubled by racism, I was met with unfathomable kindness and goodness from all quarters, black and white. So, back then, 12-year-old me set out to pass it on in the ways I could, from petitioning the City of Birmingham to provide free lunches in the summers for kids who would be eligible for free lunch during the school year to canvassing on behalf of Richard Arrington’s successful bid to become Birmingham’s first African American mayor. And throughout my life, this faith in humanity that was forged there has been reinforced and rewarded in more ways than I can count.

Today, this same sentiment, a determined belief in us, is woven into the foundation of my ideas about societies — how they change, why they end, and what it takes to become, as President Lincoln described, “a nation that can endure”. But getting to a better place requires unearthing the system beneath the symptoms of an ailing society. That’s what Krishnalal Shridharani did.

In War Without Violence, he both systematized Gandhi’s revolutionary approach to social change and made it accessible to Westerners and in doing so, altered the course of American Civil Rights. Icons like Bayard Rustin, George Houser and Pauli Murray came across Shridharani’s just-published doctoral thesis in 1939 and were all profoundly impacted by it. At the time, the future Rev. Dr. King was ten years old.

Fast-forward to 1955, when Montgomery’s prominent civil rights veterans, from the Montgomery NAACP to the local chapter of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, the first chartered African American labor union, selected a 26-year-old Martin Luther King to be the face of the newly established Montgomery Improvement Association, the organizing vehicle for the boycott.

We know much of the story from there — Rosa Parks, sit-ins, Freedom Rides, Birmingham Jail, March on Washington, Selma, the Civil Rights Act, the Voting Rights Act and the Poor People’s Campaign. Not to mention all that came after, everything from the Rainbow Coalition and women’s rights to same-sex marriage and the 2020 protests. All this work shares one thing in common — the work of inclusion.

Our Defining Moment

Looking back at history, we get how segregation worked — how it used racial grouping to determine all aspects of people’s lives. But what we miss is how we replaced racialized barriers with economic ones — everything from state legislatures that don’t pay legislators enough to live on, which means that, practically, only people of means can serve in public office, to exclusive clubs with exorbitant fees that prevent most people from joining. But this isn’t just economic. The same tactics undergird all forms of exclusion, from political to religious, social to cultural.

In This Land Is Your Land, I describe how it’s not just ancient societies like Rome or the Mongol Empire that end:

Societies, like everything else, exist in perpetual states of dynamism. The question is not whether they’ll face challenges that could be their undoing. They will, many times over. Whether confronted by rivals, impacted by disease, visited by catastrophe or simply worn down by the sum of their own choices, one thing human history proves is that any society that refuses to change is one that won’t last.

And while like any other conversation about death, we tend to find the idea of societies having a life cycle or coming to an end uncomfortable, the concept shouldn’t be so surprising to us. After all, we’ve seen the end of the USSR and the death and birth of all kinds of countries in our lifetime, and even our own Civil War was waged to reverse Southern states’ decision to form the Confederate States of America.

In reality, each generation faces choices that may very well make them that civilization’s final one, whether they recognize that about themselves or realize the significance of the choices they’re making. Avoiding this unfortunate fate begins with grasping what Martin said about how things are bound together, that all of life is “caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny,” and that “whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly.”

Because though we think of ourselves as separate, each of us is inextricably linked to the rest of us, and our generation to the ones before and after it. Once we realize this, we grasp that our society, like the biosphere, isn’t just something we can take from, but that it’s an ecosystem; one we must tend to and care for if we want to survive. This is essentially what generativity looks like.

Our growing stress fractures have led us to a decisive inflection point, one where we get to decide three critical questions; 1) whether we’ll be a nation committed to the well-being of just some of us or all of us, 2) whether we’ll be governed by we, the people, or by a faction thereof, and 3) whether we’ll address the growing gap between our systems and ourselves by pulling people backward or propelling society forward.

This is our generation’s defining moment, one where, together, we can form a more perfect union, becoming a better place, one where ”ain’t nobody crying, ain’t nobody worried.” And if we can do this; if we can learn to see everyone’s inherent beauty and worth, if we can grasp the truth of how we’re all intrinsically interconnected, and if we can summon the strength to change, to integrate DEI into our societal DNA, we do far more than make the spaces around each of us better. We create a future for us all.

“I know a place,” Mavis sang. “I have a dream,” Martin declared. They were both talking about the same thing.

—

The DEI Chronicles is a five-part series about diversity, equity and inclusion, and the importance of us incorporating these virtues into every aspect of our society if we want to become a nation that can endure. ”I’ll Take You There” is the first article in the series.

—

RD Moore is an artist, minister, lifelong social activist, emancipationist and founder of the Mary Moore Institute for Diversity, Humanity & Social Justice (MMI). He credits the people who crossed his path starting in his formative years in post-Civil Rights-era Birmingham for the person he’d become and for his unyielding faith in who we can be together. Known for his intimate storytelling and insightful understanding, his work continues to explore that fertile space where diversity, spirituality and humanity all intersect. His blog, Letters from a Birmingham Boy, can be found here.