The DEI Chronicles (Part 4 of 5): “She Works Hard for the Money”

What the people we hire tell us about the recruitment system we've built.

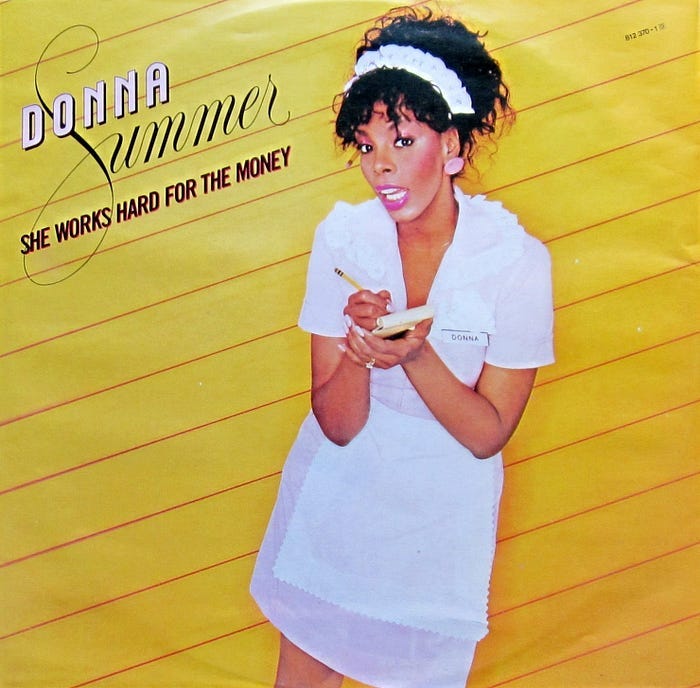

“She works hard for the money, so hard for it, honey. She works hard for the money, so you’d better treat her right.” — Donna Summer, She Works Hard for the Money

Onetta, Mary and Margie

In a 1986 interview, Donna Summer, the Queen of Disco explained how she’d come up with the idea that would evolve into one of her biggest hits three years earlier. She was attending Julio Iglesias’ Grammys after-party at West Hollywood restaurant Chasen’s when she startled the washroom attendant, Onetta Johnson, who apologized for having dozed off. Onetta explained she was exhausted from working two jobs. “I looked at her, and my heart just filled up with compassion for this lady,” Donna said, “And I thought to myself, ‘God, she works hard for the money.’”

She went back to her table, wrote down that thought, along with Onetta’s name and the anthem of hard-working women everywhere was born. And Onetta, the woman who inspired it? She was not only referenced by name in the song’s lyrics (“Onetta, there in the corner, stands, and wonders where she is. It’s strange to her — some people seem to have everything”), she appeared on the album’s back cover along with Donna herself.

I was a freshman in college when I heard the song, and it immediately took me back to my early childhood in the household of the grandparents who raised me, and of my grandmother Mary coming home from working as a domestic, exhausted. I remember her sitting there on the sofa, soaking her feet in warm water and Epsom salts as she and four-year-old me exchanged stories about our days. In Me and Mary’s Dock of the Bay, I described similar early childhood memories:

For some reason, I loved the song, (Sittin’ on) The Dock of the Bay, by Otis Redding. Something about the music and melancholy vocals spoke to me, and still do. Though I couldn’t yet read “big words”, I could recognize this single by the symbol and (carefully!) put it on. I’d then pull up my stool next to the stereo and listen. When it reached the end, I’d start it over. I remember sitting there, trying to understand with my 3-year-old mind what a “docadabay” was; this thing that he was sitting on. “I wonder if it’s like my stool,” I pondered.

I would often go in and grab my grandmother by the hand and silently pull her into the living room, with her asking, “What is it, Baby?” I’d have her sit down on the couch and I’d lay next to her with my head in her lap, and we’d listen. Sometimes, tired after a long day of work, she’d fall asleep, and I’d stay there, knowing that if I did, she’d get a bit of rest.

Mary, like Onetta, worked hard for the money. Then, there’s Margie, an extraordinary woman who I’d first hear about from her great-nephew Jason. He thought I’d want to hear her amazing story from her. And boy, was he right. An elegant, yet maternally warm African American woman who immediately brought Mary to mind, Margie had served as her Anglo American boss’s personal assistant for his entire career; from the time he was a fresh-faced MBA in the 60s through his ascension to the role of President and CEO of his family’s company. Throughout her years working there, her responsibilities had grown to the point where, when people ran up against a truly big problem, they sought out Margie.

She was also highly regarded, and many thought that if there was one person who was indispensable, it was her. She was on a first name basis with every board member, had given advice on every executive hire, had effectively worked behind the scenes to smooth over issues with some of their biggest clients, and since she was the one person brave enough to tell the CEO when he was wrong, everyone came to her. But Margie, after being at the company longer than many of its junior executives had been alive, upon her retirement, made a salary of $35,000 and had none of the stock options routinely awarded to those executives she mentored.

Twenty-odd years prior, when the world was a very different place, she’d informed her boss of her interest in moving into a management position, citing her extensive experience doing far more than fetching his coffee. However, her boss, who’d also become a dear friend, politely dissuaded her from exploring that further; warning that as a woman and an ethnic minority, not only were her chances extremely unlikely, but that pursuing that direction could make her a target in other ways; including endangering the job she currently held. So Margie kept quiet and kept her job. She cared for her family and continued to work as her boss’s informal number two; increasingly taking on responsibilities that far exceeded her station.

Margie was incredibly and unusually fortunate. Nearing retirement, she discovered that her now former boss had negotiated a deal that provided her with a pension based on an executive salary, and had lobbied the board for additional stock holdings and a golden parachute for Margie. They overwhelmingly agreed. Understandably, Margie was speechless. But her former boss told her that everything she’d been awarded was her due; and that in a better world, she would have held the title “Chief Administrative Officer”.

So Margie, instead of subsisting on a secretary’s savings, had far more financial resources in her retirement than she had in all her working years combined. But her story, like so much of the broader American story, is bittersweet. The friendship between these two people is heartwarming. Margie’s perseverance and resilience are inspiring, and the fact that her former boss was willing to fight so hard for her moves us.

But at the same time, it’s saddening that fighting so hard to see her treated fairly was even necessary. Then there’s all the other Margies out there whose stories have a decidedly different ending; often struggling to survive solely on Social Security. These immensely talented people gave their best to their employers their entire careers, only to be left with so little in return.

Edward and Wilma

Some years ago, I was brought in to advise a company that was struggling to diversify its workforce. According to them, they were having trouble finding qualified candidates who also brought diversity. They thought the problem was with the talent pool.

But anyone who works in this field knows that there’s no shortage of diverse talent out there — whether women, ethnic minorities, members of the LGBTQ+ community, people with learning differences, who are from low-income backgrounds, who never went to college and so forth — people who, if given the chance, would be extraordinary. This means that the problem lies either with us, our unspoken resistance to inclusion, our processes, or both.

In this case, there was strong commitment to diversity across the board and their commitment was genuine. So, I moved on to process, which netted a number of key insights including how by relying on their personal networks, they tended to draw people who were culturally similar to those already working there, so few diverse candidates were even up for consideration.

They were also screening out all kinds of diversity because of arbitrary criteria like advanced degrees while not accounting for all the other ways one could have become a great fit for the role. But perhaps most importantly, their interview process placed a lot more weight on easy fit with their already established culture than on an applicant’s unique value add.

I facilitated a discussion among the senior team about how our unconscious assumptions can, despite our intentions, result in a process that’s compromised from the start, then shared findings from work I and others had done where we worked backwards from things like job profiles, schedules, where positions were posted and how interviews were conducted to gain a picture of who those processes defined as their ideal candidate.

Through this, we discovered an important insight — that despite genuine efforts to diversify, the overall jobs market itself has been geared toward its own ideal applicant, and is designed to attract, employ and advance candidates that fit this unspoken, very homogeneous profile. This one insight, that, personally, we can be completely devoid of bias and even anti-bias, but still be using processes that perpetuate it, was powerful.

“It’s strange to her,” Donna Summer sang about Onetta, “Some people seem to have everything.” Because so much of what made the difference between those who have everything and those with nothing has little to do with how hard they work, but rather, whether their traits are valued or disparaged, whether or not they’re reflective of the system’s true ideal candidate. With that in mind, meet two such composites — “Edward Executive” and “Wilma Worker”:

Edward Executive

It’s not news to any of us that we live in a society where it is more advantageous to be able to identify as white than as of color. People fresh off the boat over a century ago figured this out, as had many of us today; sometimes even before entering first grade. This perception automatically elevates certain kids and diminishes others from childhood on.

Similarly, upon reaching adulthood, studies overwhelmingly confirm a significant bias toward Anglos in the hiring process. So, in this composite, Edward Executive is Euro American. But that’s not all: As is indicated by the name, Edward is both male and most likely bound for the executive suite; if he’s not there already. Additionally, Edward has a number of other advantaging traits: He’s straight and is considered a man’s man. He’s into yachting and golfing, private clubs and cigars.

He’s married and the father of two. He’s classically attractive, tall enough and has no obvious physical “defects”. He’s an Ivy grad (though not necessarily at the top of his class), was a business major, on the crew team and a member of a fraternity or secret society. His parents are both well-educated, and he grew up in a high-income household where his dad held a country club membership and his mom did charity work — all of which gives him significant contacts for sales and fundraising.

Edward is Christian — either mainline protestant or Catholic, though not excessively devout. He owns his home (which he bought with a sizeable down payment from his parents as part of his inheritance), and while he sees his extended family on occasion, they’re not a regular part of his daily life.

Within the first thirty seconds of walking into the interview room, Edward has already pulled miles ahead of his competition, and though he would never admit it, he knows this. In fact, it is unlikely that few competitors to Edward even make it into the interview room. Since most jobs are filled through personal networks, Edward likely heard about the position and was able to secure a “the job is yours to lose” interview before it was even officially posted.

Now, of course, the job market is open to far more than Edward Executive, nor do all Edwards have all these qualities. The idea behind a marketing profile such as this is that while virtually no one has all of these characteristics, the more one has in common with the ideal candidate, the more of a fit one will be perceived to be. This paradigm isn’t just operating in the background: it’s shaping interviewer perceptions the moment the candidate walks in the door; and is equally at work in the screening process — whether on purpose (passing over candidates with ethnic-sounding names) or by mistake (assuming that those from Ivy schools are better educated).

It is at work in decisions about where job announcements are posted and in the design of the job profiles themselves. The list of requirements is often based on credentials (degrees, former job titles, certifications, etc.) rather than on actual capabilities. Likewise, “fit” is based on culture established by previous hires rather than a reflection of who the company wants to be or what the emerging market looks like.

When it comes to salary negotiation, the benchmark is likely the candidate’s last salary, and jobs that require a strong personal network (sales and fundraising) are routinely priced higher than other equally, and sometimes more important jobs. In all these areas, Edward has an advantage; the very infrastructure of the jobs market has been designed for him. So, any company that is serious about attracting and retaining diverse talent will need a new candidate profile, and once they have that, they will then need to determine how to create an employment infrastructure and environment that attracts that candidate and allows them to thrive. Which leads to “Wilma Worker”.

Wilma Worker

Wilma is, in many ways, Edward’s archetypal opposite. She’s a woman, an ethnic minority, a single mother of three kids, and she’s paying rent instead of a mortgage. Her household includes another adult family member — her mother — who helps raise the kids and take care of the house; given the long hours that Wilma works. Wilma started working in high school. She managed to graduate from a state university; accomplished through evening and weekend classes starting at the local junior college; all while working full-time.

Wilma grew up in a low-income, but loving home, and though she has a very strong extended family network, none of them would have the discretionary wealth or income to allow her to succeed as a salesperson or fundraiser, or to gift her a down payment on a home. Like Edward, she spends her entire life making investments, but instead of in a 401K, it’s in people.

It was Steven Nieswander, the team’s finance guru, who both came up with the idea of basing this composite on a real-life person, and who suggested that we name it Wilma; after real-life Wilma Jones; a woman who worked tirelessly for nearly thirty years to feed and offer love to thousands of Columbia University students. Steven saw Wilma almost every morning during his graduate school years, and this is how he described her:

“The Wilma I knew was the fry cook at the student cafeteria at Columbia University. She’d begin each weekday for over 22 years at 5:00 AM in her apartment in the Bronx. She arrived on campus at 7:00 AM in order to prepare the ingredients for the omelets and make the batters for the cafeteria’s pancakes and waffles. Once the dining hall opened, she was at the grill for the entire morning, making omelets and eggs. Wilma didn’t take a break the entire time she was at work, and her dedication showed in other ways.

One year, she cut her hair in order to do her job better. “I don’t know if you’ve ever used a grill before,” she’d say, “But when I’m behind there, it gets hot. I kept getting sweat and oils dripping down into my face when I had hair, so I decided it was time to cut it off.” She received an outpouring of sympathy from students who thought she was suffering from cancer. “I’m not sick,” Wilma would say, “I’m just hot!” Wilma doesn’t have children of her own. She said she didn’t have time for them. “What would I do with kids, with all these that I have here,” referring to all us students. “I’m like Old Mother Hubbard.”

On her twentieth anniversary, the university honored Wilma by naming her grilling station “Wilma’s Grill” and erecting a large golden sign above her. I got to know Wilma really well over my time at Columbia and told many friends about her legendary grilling station. One Thanksgiving, Wilma realized I didn’t have anywhere to go for dinner. She invited me to join her family at her house. It was for sure one of the most memorable and delicious Thanksgiving meals I’ve ever had. Though I was not African American and had just met everyone except Wilma, they made me feel like I was part of the family.

We ate at her sister’s apartment at a large government housing complex in Queens. Wilma had helped her sister support her twin teenage sons since Wilma’s sister’s husband walked out. The twins often spent afternoons and weekends with Wilma, since she went to work early in the morning and was home around the time the boys got out of school. Also in attendance was Wilma’s brother, a recovering alcoholic who demanded a good share of Wilma’s patience, time, and no doubt money as well.

When I arrived Thanksgiving day, it was clear that Wilma and her sister had been cooking for days. The counters, kitchen table, and all available surfaces in the living room were lined with aluminum heating trays fueled by flaming Sterno containers, or domed-up plates of desserts. There was fish, ham, chicken, and, of course, turkey. There were vegetables galore and pumpkin, sweet potato, and apple pie, along with all kinds of cookies. We sat together, eating, saying what we were thankful for, and laughed a lot. It was a wonderful day, and it was amazing to me how far Wilma and her sister made their modest incomes go to making a truly bountiful evening.”

So much of the dedication, work ethic, and most importantly, heart that was so eloquently captured in Steven’s recollection of real-life Wilma holds true for so many Wilmas, Onettas and Marys out there; the true heart and soul of so many organizations.

Like Edward Executive, not every Wilma Worker is an ethnic minority. They could be from the thousands of Euro American families that have been trapped in poverty for generations. They could be male (this profile could easily have been named “Willis Worker”), a member of the LGBTQIA+ community, a person with something we’d normally consider a disability, a follower of a different religion, someone who never attended university (public or otherwise), any person from a low-income background, or with a conviction on their record.

They could be an introvert, a left-hander, someone with an “unpreferred” body type, someone who speaks English as a second language, an undocumented immigrant or myriad other ways one might deviate from the norm. But one thing’s for sure — in today’s market, we don’t need to assess a candidate’s capabilities to know whether they’ll get the job. All we need to know is whether society considers them an Edward or a Wilma.

Better Treat Her Right

HR research, including studies that show how third parties can predict, with startling accuracy, whether a person will be offered a job by watching the first thirty seconds of an interview and how gender bias is all but eradicated in blind orchestra auditions teach us two things. First, they’re not making it up. Our employment structure really does have an ideal candidate, and it’s not Mary, Onetta or Margie. And second, if we choose to, we can do better.

It starts with awareness, recognizing how Donna’s admonition, “So, you better treat her right,” isn’t necessarily front-of-mind for us. But it’s not that we’re intent on treating her wrong. It’s more that we’re simply unaware of all the ways the system is structured to do exactly what it’s doing — take advantage of her — starting with that first job offer and continuing through everything that happens after, from the behaviors performance reviews are designed to reward to how we determine which roles are eligible for bonus pay, company cars or expense accounts.

Take the practice of considering salary history to determine pay for new positions. Simply put, our pay in previous jobs has no bearing on what we should be paid for doing this one. This job has a fair rate of pay, and as employers, we’re obligated to determine what that is, based on the particulars of this job. In theory, using salary history to determine pay for new positions seems reasonable, but practically, it advantages people who’ve had higher-paid roles.

Then, over time, it exacerbates this wage disparity. Studies show that two recent MBAs, one male and one female, based just on gender alone, would be offered significantly different salaries for their first post-business school jobs. The female would make, on average, 70% of what the male would be paid; even if they were both hired for the same position. Then, due to salary history considerations, every time they change companies, their previous salaries would be the baseline for what they’d be offered in their new role. By the end of their careers, the male MBA could easily end up with an annual salary twice that of the female MBA based solely on this practice.

There’s no easy fix for this. The flaws are built into the machinery itself. Each practice that facilitates this kind of unfairness, every process that results in us not “treating her right” will need to be identified, examined and corrected. It’s hard work. But it’s also doable. Take social media software provider Buffer.

In 2013, just two years into its existence, the company made a number of radical decisions, including going fully remote (7 years before COVID) and adopting a standard of transparency, including with respect to compensation and how it’s determined. Since then, hundreds of companies have followed in their footsteps, using variations of their salary calculator. Describing themselves as an “open” company, Buffer employees, across the board, are immensely satisfied with the approach.

Or, take food justice nonprofit Farming Hope, one of a growing number of organizations who have re-envisioned their chief executive role by splitting it which helps Wilma in two ways: first, she can tackle a meaningful role while still being able to manage a balanced home life, and second, the co-CEO can be someone who might not have Wilma’s lived experience with the problems groups like Farming Hope exist to solve, but who might be exceptional at things that might not be Wilma’s strengths, like being an effective fundraiser. The organization gets the best of both worlds, but only because they did the work to restructure how things work.

We can do better. We can become aware of the ways we’re unwittingly perpetuating bias, and in the process, validating it. We can recognize how it’s been embedded in our infrastructure. And, perhaps most importantly, we can do the work to realign our infrastructure to reflect our values. In doing so, we not only live up to our virtues; we create a corporate environment where everyone, from Edward to Wilma, can thrive. They work hard for the money, so we’d better treat them right.

—

The DEI Chronicles is a five-part series about diversity, equity and inclusion, and the importance of us incorporating these virtues into every aspect of our society if we want to become a nation that can endure. ”She Works Hard for the Money” is the fourth article in the series.

RD Moore is an artist, minister, lifelong social activist, emancipationist and founder of the Mary Moore Institute for Diversity, Humanity & Social Justice (MMI). He credits the people who crossed his path starting in his formative years in post-Civil Rights-era Birmingham for the person he’d become and for his unyielding faith in who we can be together. Known for his intimate storytelling and insightful understanding, his work continues to explore that fertile space where diversity, spirituality and humanity all intersect. His blog, Letters from a Birmingham Boy, can be found here.