I was the very definition of “comic book geek” growing up. My favorite character was Marvel’s Daredevil, who, in an act of heroism as a boy, was blinded and who used his remaining now hyper-acute senses to compensate during his heroics. Then, there was DC’s Batman, who, in a group comprised of god-like aliens, an actual Amazonian demi-goddess, an amphibious king of the seas, and a guy with a ring that could do almost anything, was diverse in that he had no superpower; other than his combination of intelligence, determination and discipline.

I loved how both Daredevil and Batman stood up for others; even against foes that were so much stronger, faster and physically more powerful. They inspired me to want to do the same, and their influence on me was no doubt part of why New York City, both Daredevil’s Hell’s Kitchen and Batman’s Gotham, took on such mythic qualities.

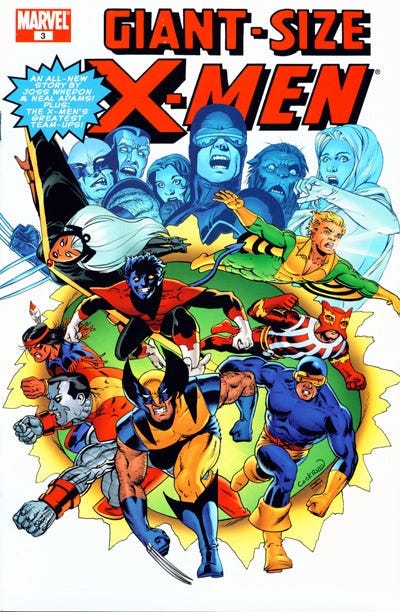

I loved those epic stories of good prevailing over evil. But for all the ways I admired them, they still existed as characters in another world. That is, until 11-year-old me came across Chris Claremont’s reboot of the X-Men on a comic book stand in Ensley Apothecary, a local drug store. That experience was something else entirely.

Even back then, it was the diversity of this team that fascinated me; as did the fact that they were mutants; people who, because they were born different, were met with distrust and disgust. I couldn’t understand why they were classified as a different race simply because their mutation was genetic, rather than caused by a bite from, say, a radioactive spider, cosmic rays or super-soldier injection. But that’s the way of bigotry; it never makes any real sense.

In the world of superhero comics, virtually everyone, including aliens from the planet Krypton, presented as white. And American. Besides the Black Panther, I’d never seen a non-American hero in a comic book, nor, to my knowledge, had there ever been a dark-skinned heroine. That was also the case with the original team of X-Men. But on this new team, the only American was of the Native variety, a hero code-named Thunderbird. Everyone else was a foreign national, hailing from Japan (Sunfire), Germany (Nightcrawler), Ireland (Banshee), Russia (Colossus), Kenya/Egypt (Storm), and Canada (Wolverine). Neither I nor the world had ever seen anything like them. For me, it was love at first sight.

While I might not have been able to put it into words at the time, even the looks ranging from alarm to horror on the faces of the former team comprised solely of white-identifying Americans, as this new, diverse, international team quite literally broke through the page spoke to me.

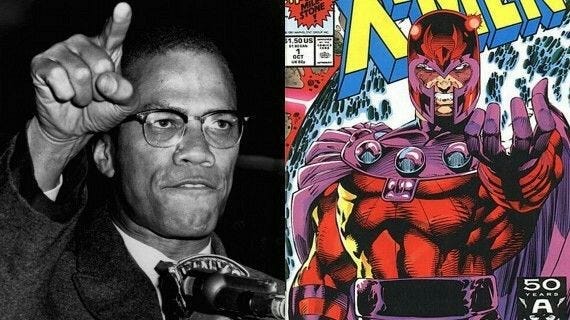

But what really shifted these comics from being about that world to the one I lived in was the introduction of Professor X and Magneto, Charles Xavier and Erik Lehnsherr; two former best friends who’d philosophically splintered over the right way to go about accomplishing the same goal, saving their people. Erik, who controlled magnetism, was Jewish and a Holocaust survivor. Charles, a powerful telepath and paraplegic; confined to a wheelchair. Not only were they both mutants, and thus deemed not fully human; they were each diverse in other ways.

Then, there was me; this economically disadvantaged, ethnic minority kid growing up in Birmingham, and fighting, in whatever ways I could, to make a difference. But unlike the comics, it often felt like all that I and others were doing couldn’t stop the bad things. In Me and Mary, I describe how one of my earliest memories was Martin’s death. I was barely three years old, and I didn’t understand why all the adults around me were weeping so profusely. I remember watching a man sit down on the curb outside our house, head in hands and shoulders shaking with silent sobs. I didn’t know what had happened, but I knew it was awful.

Perhaps it was because of that time and place and how it shaped me that I’d been drawn to Martin’s books, speeches and sermons from the time I could read. So, it was quite easy to see him in Charles and their shared dream of peaceful coexistence. Especially when I saw that contrasted by Erik, who’d witnessed the worst in humanity, who’d seen everyone he’d ever known and loved slaughtered, and who’d vowed, “Never again”. He would save his people “by any means necessary.” I’d always loved Martin. But it was through Erik that I’d learn to truly see, and understand, Malcolm.

Intelligent, charismatic and handsome El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz, known the world over as Malcolm X, would, in his 39 years, become one of the most influential people of his generation, if not the century. Malcolm, born “Malcolm Little” in Lincoln, Nebraska, in 1925, shared a birth year with Medgar; both of whom were only three years older than Martin. All three, Medgar, Martin and Malcolm, would be assassinated before reaching 40.

As a society, we’ve struggled mightily against the truths Malcolm confronted us with; constantly contrasting him against Martin, as if they were not both speaking of the same societal ills. “I watched two men coming from unimaginably different backgrounds, whose positions originally were poles apart, driven closer and closer together,” said James Baldwin in I Am Not Your Negro, who knew both them and Medgar personally, after their deaths. “By the time each died, their positions had become virtually the same position. It can be said, indeed, that Martin picked up Malcolm’s burden, articulated the vision which Malcolm had begun to see, and for which he paid with his life.”

Young Malcolm grew up in a household where both of his parents were social activists; specifically through their involvement with the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA). His father, Earl, both received death threats from the Ku Klux Klan and was constantly harassed by the Black Legion; an ironically named white supremacy militia that many believe was the cause of Earl’s ostensibly accidental death.

Malcolm’s mother, Louise, was Grenadian/Scottish; her African American mother raped by a man who would never be a father to her. Malcolm was 6 when Earl died, and when Louise was hospitalized a few years later, the kids were sent to foster homes. Malcolm would spend the rest of his childhood being shuttled from place to place. Though academically gifted, he would drop out of high school after a white-identifying teacher told him that practicing law, his aspiration at the time, was “no realistic goal for a nigger.” (She clearly didn’t see the likes of Pauli and Thurgood coming.)

After trying his hand at any number of the only jobs available to someone in his position, Malcolm, at 18, took off for New York City, and after landing in Harlem, found himself increasingly engaged in all manner of illegal activities; from drug dealing to gambling to racketeering. Two years later, after participating in a series of burglaries targeting homes owned by wealthy Anglos, he was arrested while picking up a stolen watch he’d left at a shop for repairs, and sentenced to ten years in prison.

Ironically, it was there in prison that Malcolm would begin to liberate himself. First, he met fellow prisoner and self-educated scholar, John Bembry, who Malcolm would later describe as “the first man I had ever seen command total respect … with words”. It was John who would nurture both his thirst for knowledge and his voracious appetite for reading. Second, at the encouragement of his siblings, an initially resistant Malcolm began to explore the teachings of the Nation of Islam, at that time, a new religious movement preaching black self-reliance and self-improvement.

As his brother Reginald began tutoring him in the Nation’s teachings and practices, Malcolm started to see how his own life story; particularly, his dealings with those identifying as white (from his grandmother’s rape, to having his childhood home burned down, to his father’s suspicious death, to his own personal encounters) all confirmed a core belief of the faith; that white people are devils. Upon reflection, he concluded that every relationship he’d had with any member of the whiteness franchise had been tainted by dishonesty, injustice, greed, and hatred.

Later that year, Malcolm would write Elijah Muhammad, leader of the Nation of Islam directly, and Muhammad would advise him to renounce his past, submit to God, and turn his back on the destructive behaviors of his youth. This ongoing relationship with Muhammad would lead to Malcolm’s wholehearted embracing of the Nation’s teachings and subsequently, becoming arguably the movement’s most influential member. Two years later, while he was still in prison, the FBI would open a file on Malcolm after he wrote a letter to President Truman voicing his opposition to the Korean War and declaring himself a communist.

This was also the year, 1950, that a 25-year-old, energized, impassioned and incredibly articulate Malcolm Little became Malcolm X: Muhammad instructed all members of the Nation to reject their family names and, until he was ready to reveal their original, true name, to use “X”, intended to be a temporary placeholder instead. Malcolm followed suit, but for him, it became much more; explaining that the “X” symbolized the true African family name that he could never know. Malcolm would, in his autobiography, write, “For me, my ‘X’ replaced the white slavemaster name of ‘Little’, which some blue-eyed devil named Little had imposed upon my paternal forebears.”

Upon parole in 1952, Malcolm jumped into the Nation with both feet; ascending rapidly, opening several chapters and personally recruiting thousands of members. Recognized as the Nation’s rising star, Malcom would simultaneously mesmerize and scandalize the country during his interview segments in The Hate That Hate Produced, a 1959 documentary about Black Nationalism in general and the Nation of Islam in particular; produced by Mike Wallace of 60 Minutes fame, and Louis Lomax, America’s first African American TV journalist. When Louis, interviewing Malcolm, asked him if all white people were evil, Malcolm asserted that white people, as a collective, were evil.

“History is best qualified to reward all research, and we don’t have any historic example where we have found that they have, collectively, as a people, done good,” he said, on national television, in a time when things like this weren’t loudly thought, let alone spoken. This was a game-changer. Despite the constant barrage, from the likes of George Wallace, Jesse Helms and Olin Johnston, all mentioned just in the last chapter, everyone from ministers to Supreme Court justices, all declaring African Americans inferior and comparing them to apes and cockroaches, no one had ever dared villainize them in return. Until Malcolm.

When he was asked about the teaching methods of the University of Islam and other Nation schools, Malcolm denied the accusation that they taught black children to hate. He, instead, asserted that these kids were being taught the exact same things that white students were being taught in every respect, including to value themselves; something their educations, historically, hadn’t done. It was like America was stacked on dynamite and Malcolm had just lit the fuse.

Facing condemnation from all quarters, he was accused of being everything from hatemonger to black supremacist, racist, violence-seeker, segregationist, and a threat to improved race relations. At the same time however, his message increasingly found an audience; not just among African Americans, but among Americans as a whole.

His inflammatory style notwithstanding, Malcolm’s plainspoken eloquence, deep-rooted conviction, razor-sharp intellect and undeniable charisma proved to be a potent combination, and before long, he’d become the face of the Nation of Islam. Malcolm, at the time, was also scathingly critical of the Civil Rights movement, describing its leaders as “stooges” of the white establishment and referring to the historic 1963 March as “the farce on Washington”; saying he did not know why so many black people were excited about a demonstration “run by whites, in front of a statue of a president who has been dead for a hundred years, and who didn’t like us when he was alive.”

What few people knew, however, was that Malcolm and the Nation, and particularly, Malcolm and Muhammad, a man he loved as a father, were already on divergent paths. After escalating, variegated conflicts between them, Malcolm would, on March 8, 1964, publicly announce his break from Muhammad and the Nation, and that though he still considered himself a Muslim; he felt he’d traveled as far as he could with that branch of it.

He stated that he was planning to launch his own organization to “heighten the political consciousness”, and that he was looking forward to working with other civil rights leaders; that both Elijah Muhammad and the teachings of the Nation, to which he’d fully committed, had prevented him from doing so, or even wanting to do so in the past. And Malcolm would immediately come out swinging. Two weeks later, both he and Martin, meeting for the first and only time, would travel to Washington to hear the Senate debate the Civil Rights bill.

The behavior of the “Southern Bloc” of 18 Democrats, along with one Republican Senator would disgust Malcolm. Led by Georgia Democratic Senator Richard Russell, the contingent attempted to filibuster the bill’s passage, with Russell saying, “We will resist to the bitter end any measure or any movement which would have a tendency to bring about social equality and intermingling and amalgamation of the races in our [Southern] states.”

A few days later, on April 3, 1964, Malcolm would fire back with what would come to be considered one of the most compelling public addresses of this era of compelling public addresses. The intentionally and provocatively titled, The Ballot or the Bullet, part history lesson and part sermon, gave a retrospective of African American history in the United States from slavery forward, with an unapologetic fervor and brutal honesty that’s never lost relevance.

In 1999, it was ranked 7th out of the top 100 American speeches of the 20th century, based on recommendations from 137 leading scholars of American public address who were asked to recommend speeches on the basis of social and political impact, and rhetorical artistry. The speech was a scathing indictment of American democracy. What follows is a significantly redacted version of the 53-minute speech. You can read it in its entirety here.

“The question tonight, as I understand it,” Malcolm began, ”Is, ‘The Negro Revolt and Where Do We Go from Here?’ or ‘What Next?’ In my little humble way of understanding it, it points toward either the ballot or the bullet.” Then, he dove in head-first:

Although I’m still a Muslim, I’m not here tonight to discuss my religion. I’m not here to try and change your religion. I’m not here to argue or discuss anything that we differ about, because it’s time for us to submerge our differences and realize that it is best for us to first see that we have the same problem, a common problem, a problem that will make you catch hell whether you’re a Baptist, or a Methodist, or a Muslim, or a nationalist. Whether you’re educated or illiterate, whether you live on the boulevard or in the alley, you’re going to catch hell just like I am. We’re all in the same boat and we all are going to catch the same hell from the same man. He just happens to be a white man… All of us have suffered here, in this country, political oppression at the hands of the white man, economic exploitation at the hands of the white man, and social degradation at the hands of the white man.

Now in speaking like this, it doesn’t mean that we’re anti-white, but it does mean we’re anti-exploitation, we’re anti-degradation, we’re anti-oppression. And if the white man doesn’t want us to be anti-him, let him stop oppressing and exploiting and degrading us… I’m not a politician, not even a student of politics; in fact, I’m not a student of much of anything. I’m not a Democrat. I’m not a Republican, and I don’t even consider myself an American.

If you and I were Americans, there’d be no problem. Those Honkies that just got off the boat, they’re already Americans; Polacks are already Americans; the Italian refugees are already Americans. Everything that came out of Europe, every blue-eyed thing, is already an American. And as long as you and I have been over here, we aren’t Americans yet. Well, I am one who doesn’t believe in deluding myself. I’m not going to sit at your table and watch you eat, with nothing on my plate, and call myself a diner. Sitting at the table doesn’t make you a diner, unless you eat some of what’s on that plate…

No, I’m not an American. I’m one of the 22 million black people who are the victims of Americanism. One of the 22 million black people who are the victims of democracy, nothing but disguised hypocrisy. So, I’m not standing here speaking to you as an American, or a patriot, or a flag-saluter, or a flag-waver — no, not I. I’m speaking as a victim of this American system. And I see America through the eyes of the victim…

I was in Washington, D.C., a week ago Thursday, when they were debating whether or not they should let the bill come onto the floor. And in the back of the room where the Senate meets, there’s a huge map of the United States, and on that map it shows the location of Negroes throughout the country. And it shows that the Southern section of the country, the states that are most heavily concentrated with Negroes, are the ones that have senators and congressmen standing up filibustering and doing all other kinds of trickery to keep the Negro from being able to vote. This is pitiful…

These senators and congressmen actually violate the constitutional amendments that guarantee the people of that particular state or county the right to vote. You don’t even need new legislation. Any person in Congress right now, who is there from a state or a district where the voting rights of the people are violated, that particular person should be expelled from Congress. And when you expel him, you’ve removed one of the obstacles in the path of any real meaningful legislation in this country.

I say again, I’m not anti-Democrat, I’m not anti-Republican; I’m not anti-anything. I’m just questioning their sincerity, and some of the strategy that they’ve been using on our people by promising them promises that they don’t intend to keep. That’s why, in 1964, it’s time now for you and me to become more politically mature and realize what the ballot is for; what we’re supposed to get when we cast a ballot; and that if we don’t cast a ballot, it’s going to end up in a situation where we’re going to have to cast a bullet. It’s either a ballot or a bullet….

So it is not necessary to change the white man’s mind. We have to change our own mind. You can’t change his mind about us. We’ve got to change our own minds about each other. We have to see each other with new eyes. We have to see each other as brothers and sisters. We have to come together with warmth so we can develop unity and harmony that’s necessary to get this problem solved ourselves…

We will listen to everyone. We want to hear new ideas and new solutions and new answers. And at that time, if we see fit then to form a Black Nationalist party, we’ll form a Black Nationalist party. If it’s necessary to form a Black Nationalist army, we’ll form a Black Nationalist army. It’ll be the ballot or the bullet. It’ll be liberty or it’ll be death… You let that white man know, if this is a country of freedom, let it be a country of freedom; and if it’s not a country of freedom, change it.

Last but not least, I must say this concerning the great controversy over rifles and shotguns. The only thing that I’ve ever said is that in areas where the government has proven itself either unwilling or unable to defend the lives and the property of Negroes, it’s time for Negroes to defend themselves. Article Number Two of the constitutional amendments provides you and me the right to own a rifle or a shotgun.

It is constitutionally legal to own a shotgun or a rifle. This doesn’t mean you’re going to get a rifle and form battalions and go out looking for white folks, although you’d be within your rights–I mean, you’d be justified; but that would be illegal and we don’t do anything illegal. If the white man doesn’t want the black man buying rifles and shotguns, then let the government do its job. That’s all…

I hope you understand. Don’t go out shooting people, but any time–brothers and sisters, and especially the men in this audience; some of you wearing Congressional Medals of Honor, with shoulders this wide, chests this big, muscles that big–any time you and I sit around and read where they bomb a church and murder in cold blood, not some grownups, but four little girls while they were praying to the same God the white man taught them to pray to, and you and I see the government go down and can’t find who did it.

Why, this man–he can find Eichmann hiding down in Argentina somewhere. Let two or three American soldiers, who are minding somebody else’s business way over in South Vietnam, get killed, and he’ll send battleships, sticking his nose in their business. He wanted to send troops down to Cuba and make them have what he calls free elections–this old cracker who doesn’t have free elections in his own country. No, if you never see me another time in your life, if I die in the morning, I’ll die saying one thing: the ballot or the bullet, the ballot or the bullet.

Lyndon B. Johnson is the head of the Democratic Party. If he’s for civil rights, let him go into the Senate next week and declare himself. Let him go in there right now and declare himself. Let him go in there and denounce the Southern branch of his party. Let him go in there right now and take a moral stand–right now, not later. Tell him, don’t wait until election time. If he waits too long, brothers and sisters, he will be responsible for letting a condition develop in this country which will create a climate that will bring seeds up out of the ground with vegetation on the end of them looking like something these people never dreamed of. In 1964, it’s the ballot or the bullet. Thank you.

On June 19, 1964, after 60 days of filibustering by the Democratic contingent, a compromise version of the bill was finally passed by the Senate, then the House–Senate conference committee; before being signed into law by President Johnson on July 2, 1964. And President Johnson, bolstered by minority support, would win reelection by a landslide with 61.05% of the vote, making it the highest ever share of the popular vote since the Founding Fathers, and another example of how we Americans, irrespective of the lines we’ve drawn, have also found ways to come together.

In February of the following year, Malcolm would be gunned down by what appeared to be members of the Nation of Islam. But, on the 56th anniversary of his passing, a deathbed letter by former NYPD undercover cop Raymond Wood would implicate both his former department and the FBI in Malcolm’s death. “It was my assignment to draw the two men into a felonious federal crime so that they could be arrested by the FBI,” said Raymond in his letter. Those two men would turn out to be Malcolm’s personal security detail; leaving him unprotected.

Though the changes we’ve undergone would have been unimaginable in Malcolm’s day, the climate he spoke of when he prophesied that if we Americans weren’t careful, we’d produce generation upon generation of bitter fruit, was right on target. That’s an apt description as any of where we are today, partway through our Great Sociological Shift, and all that the former majorities are teaching the soon-to-be new majorities about how to treat minorities. Describing the segregationists of his day, Malcolm said, “He sees that the pendulum of time is swinging in your direction.” And he was right. That’s exactly what so many of us see today. But luckily, that’s not all. We also see hope.

For my part, I’d discover that the legacy of Malcolm X is just as potent as ever, and that heroes don’t just live in comics. Like the X-Men, Malcolm refused to be cowed or diminished, and like Magneto, there was no limit on how far he was willing to go in his fight for freedom. He, like Daredevil and Batman, had the courage and audacity to take on foes who presented as unstoppable — and stop them.

Upon his death, the majority consensus was that Malcolm had lost. But time itself would vindicate him; revealing all the ways that he, like Medgar and Martin, had, in fact, triumphed.

—

The Equalizers is an open series about people willing to take on society’s greatest powers in order to make “all are created equal” real. Malcolm X is the second article in the series.

RD Moore is an artist, minister, lifelong social activist, emancipationist and founder of the Mary Moore Institute for Diversity, Humanity & Social Justice (MMI). He credits the people who crossed his path starting in his formative years in post-Civil Rights-era Birmingham for the person he’d become and for his unyielding faith in who we can be together. Known for his intimate storytelling and insightful understanding, his work continues to explore that fertile space where diversity, spirituality and humanity all intersect. His blog, Letters from a Birmingham Boy, can be found here.